USSR Songs

Text

CLICK ON TITLE

TO PLAY & DOWNLOAD

SITES

International hymn for all Workers of the World

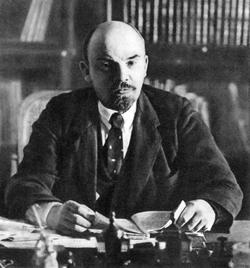

Lenin museum. Red Square, Moscow

Tasks of the New Soviet

![]() VII Comintern Congress

VII Comintern Congress

From:

RCP at http://www.mcs.net/~rwor/

Whirlwinds of Danger

By the Red Army Chorus.

A revolutionary Polish song from the 19th century

that became one of the anthems of the 1917

October Revolution in Russia.

This song has been translated into many languages

and sung by revolutionaries around the world. (In Russian)

Whirlwinds of danger are raging around us O’erwhelming forces of darkness assail Still in the night see advancing before us Red flag of liberty that yet shall prevail.

[Chorus]

Then forward, ye workers, freedom awaits you. O’er all the world, on the land and the sea. On with the fight for the cause of humanity, March, march ye toilers and the world shall be free.

Sisters and brothers in hunger are calling, Shall we be silent to their sorrow and woe? While in the fight, see our comrades are falling, Up, then united, and conquer the foe!

[Chorus]

Off with the crowns of the tyrants of favour, Down in the dust with the prince and the peer, Strike off your chains sons and daughters of labour, Wake all humanity for victory is near!

[Chorus]

_____________________________________________

From:

Canada-USSR Association, Inc. 280 Queen Street West

Toronto, Ontario M5V 2A1 977-5819

The 140 million members of Soviet trade unions make

up 99.5 per cent of all factory and office workers,

collective farmers and also the students of vocational,

specialized secondary and higher schools.

80.8 million (close to 58 per cent) trade union members

are workers and 12.3 million are collective

farmers. More than half of the members are women.

Primary organizations which form the basis of Soviet

trade unions number 706,000.

The governing body of Soviet trade unions in between

their congresses is the All-Union Central Council of Trade

Unions (AUCCTU)

Trade union activists number nearly 58 million.

The overwhelming majority of trade

union committees have no full-time officials and their

chairmen work on a voluntary basis, without pay.

More than 26 per cent of the chairmen of trade union

committees are workers and over 55 per cent

are specialists in various fields of the national economy.

Almost two-thirds of those heading trade

union committees are women and one-fifth are young people.

The prime concern of trade unions is the improvement

of working conditions and labour protection.

The technical inspectorate of trade unions,

which has aver 6,500 members, controls working

conditions and safety measures in production.

Labour safety and working conditions at places

of work are also checked by 4.6 million public

inspectors and members of labour-protection

commissions of trade union committees.

Trade unions carry out their functions of labour

protection, in particular, through control

over the compliance with labour legislation.

Each year legal inspectorates of trade unions

check nearly 30,000 enterprises, offices and organizations.

The Soviet trade unions run 564 sanatoriums,

which can accommodate 274.000 persons,

nearly 400 holiday homes and hotels, which can

accommodate 183,000 persons, and also

water and mud-cure centres, polyclinics, which

provide general health care at resorts, dietetic

canteens and other facilities.

In 1986 trade union sanatoriums and holiday

homes accommodated over 10.2 million factory

and office workers and the members of their families.

The network of sanatoriums for parents

with children grew by 7,200 places in the last

five-year period (1981-1985). These sanatoriums

can provide treatment and rest to 211,000 persons annually.

In 1986 about 17.5 million children and teenagers,

or 44 per cent of all schoolchildren,

attended the nearly 100,000 trade union camps of

different types (general summer camps,

sports and health-building camps and work-and-recreation camps).

The voluntary sports societies of trade unions

have a membership of 57.5 million.

About 32.5 million people attend various sports

sections and nearly 25 million,

health-building groups.

The athletic facilities run by trade unions can

accommodate almost ‘16 million people

a day. They include more than 3,000 stadiums,

over 15.000 gyms, about 5,000 ski

resorts, almost 250,000 athletic grounds and

soccer fields, nearly 1,400 swimming

pools and 5,900 shooting ranges and shooting galleries.

The cultural institutions run by trade unions include

23,000 community centres and houses and palaces of

culture. A total of 1,500 million visitors attend

various cultural events and hobby clubs annually.

The number of amateur

artistic companies-choral, dancing, music, drama,

painting and other groups-is nearly 570,000.

A total of 12 million people are engaged in various amateur artistic activities.

The 18,000 trade union libraries are used by 27.6 million readers.

______________________________________________________________________

|

|

CLICK HERE

Stalin's Speech Delivered at a Memorial Meeting of the Kremlin Military School January 28, 1924Comrades, I am told that you have arranged a Lenin memorial meeting here this evening

and that I have been invited as one of the speakers. I do not think there is any need for

me to deliver a set speech on Lenin's activities. It would be better, I think, to confine

myself to a few facts to bring out certain of Lenin's characteristics as a man and a

statesman. There may, perhaps, be no inherent connection between these facts, but that is

not of vital importance as far as gaining a general idea of Lenin is concerned. At any

rate, I am unable on this occasion to do more than what I have just promised. A MOUNTAIN EAGLEI first became acquainted with Lenin in 1903. True, it was not a personal acquaintance; it was maintained by correspondence. But it made an indelible impression upon me, one which has never left me throughout all my work in the Party. I was in exile in Siberia at the time. My knowledge of Lenin's revolutionary activities since the end of the 'nineties, and especially after 1901, after the appearance of the Iskra, had convinced me that in Lenin we had a man of extraordinary calibre. At that time I did not regard him as a mere leader of the Party, but as its actual founder, for he alone understood the inner essence and urgent needs of our Party. When I compared him with the other leaders of our Party, it always seemed to me that he was head and shoulders above his colleagues— Plekhanov, Martov, Axelrod and the others; that, compared with them, Lenin was not just one of the leaders, but a leader of the highest rank, a mountain eagle, who knew no fear in the struggle, and who boldly led the Party forward atong the unexplored paths of the Russian revolutionary movement. This impression took such a deep hold of me that I felt impelled to write about it to a close friend of mine who was living as a political exile abroad, requesting him to give me his opinion. Some time later, when I was already in exile in Siberia—this was at the end of 1903 received an enthusiastic reply from my friend and a simple, but profoundly expressive letter from Lenin, to whom, it transpired, my friend had shown my letter. Lenin's note was comparatively short, but it contained a bold and fearless criticism of the practical work of our Party, and a remarkably clear and concise account of the entire plan of work of the Party in the immediate future. Only Lenin could write of the most intricate things so simply and clearly, so concisely and boldly that every sentence did not so much speak as ring out like a rifle shot. This simple and bold letter still further strengthened me in my opinion that Lenin was the mountain eagle of our Party. I cannot forgive myself for having, from the habit of an old underground worker, consigned this letter of Lenin's, like many other letters, to the flames. My acquaintance with Lenin dates from that time. MODESTYI first met Lenin in December 1905 at the Bolshevik conference in Tammerfors (Finland). I was hoping to see the mountain eagle of our Party, the great man, great not only politically, but, if you will, physically, because in my imagination I pictured Lenin as a giant, stately and imposing. What, then, was my disappointment to see a most ordinary-looking man, below average height, in no way, literally in no way, distinguishable from ordinary mortals... . It is accepted as the usual thing for a "great man" to come late to meetings so that the assembly may await his appearance with bated breath; and then, just before the "great ma.n" enters, the warning whisper goes up: "Hush! ... Silence'! ... He's coming." This ritual did not seem to me superfluous, because it creates an impression, inspires respect. What, then, was my disappointment to learn that Lenin had arrived at the conference before the delegates, had settled himself somewhere in a corner, and was unassumingly carrying on a conversation, a most ordinary conversation with the most ordinary delegates at the conference. I will not conceal from you that at that time this seemed to me to be somewhat of a violation of certain 'essential rules. Only later did I realize that his simplicity and modesty, this striving to remain unobserved, or, at least, not to make himself conspicuous and not to emphasize his high position, this feature was one of Lenin's strongest points as the new leader of the new masses, of the simple and ordinary masses, of the "rank and file" of humanity. FORCE OF LOGICThe two speeches Lenin delivered at this conference were remarkable: one was on the current situation and the other on the agrarian question. Unfortunately, they have not been preserved. They were inspired, and they roused the whole conference to a pitch of stormy enthusiasm. The extraordinary power of conviction, the simplicity and clarity of argument, the brief and easily understandable sentences, the absence of affectation, of dizzying gestures and theatrical phrases aiming for effect—all this made Lenin's speech a favourable contrast to the speeches of the usual "parliamentary" orator. But what captivated me at the time was not these features of Lenin's speeches. I was captivated by that irresistible force of logic in them which, although somewhat terse, thoroughly overpowered his audience, gradually electrified it, and then, as the saying goes, captivated it completely. I remember that many of the delegates said: "The logic of Lenin's speeches is like a mighty tentacle which twines all round you and holds you as in a vise and from whose grip you are powerless to tear yourself away: you must either surrender or resign yourself to utter defeat." I think that this characteristic of Lenin's speeches was the strongest feature of his art as an orator. NO WHININGThe second time I met Lenin was in 1906 at the Stockholm Congress of our Party. You know that the Bolsheviks were in the minority at this congress and suffered defeat. This was the first time I saw Lenin in the role of the vanquished. But he was not a jot like those leaders who whine and lose heart when beaten. On the contrary, defeat transformed Lenin into a spring of compressed energy w^hich inspired his followers for new battles and for future victory. I said that Lenin was defeated. But was it defeat? You had only to look at his opponents, the victors at the Stockholm Congress—Plekhanov, Axelrod, Martov and the rest. They had little of the appearance of real victors, for Lenin's implacable criticism of Menshevism had not left one whole bone in their body, so to speak. I remember that we, the Bolshevik delegates, huddled together in a group, gazing at Lenin and asking his advice. The talk of some of the delegates betrayed a note of weariness and dejection. I recall that Lenin bitingly replied through clenched teeth: "Do not whine, comrades, we are bound to win, for we are right." Hatred of the whining intellectual, faith in our own strength, confidence in victory—'that is what Lenin impressed upon us. It wa,s felt that the Bolsheviks' .defeat was 'temporary, that they were bound to win in the very near future. "No whining over defeat"—this was a feature of Lenin's activities that helped him to rally around himself an army faithful to the end and confident in its strength. NO BOASTINGAt the next Congress, held in 1907 in London, the Bolsheviks were victorious. This was the first time I saw Lenin in the role of victor. Victory usually turns the heads of leaders and makes them haughty and boastful. They begin in most cases to celebrate their victory, to rest on their laurels. Lenin did not resemble such leaders one jot. On the contrary, it was after a victory that he was most vigilant and cautious. I recall that Lenin insistently impressed on the delegates: "The first thing is not to become intoxicated by victory and not to boast; the second thing is to consolidate the victory; the third is to give the enemy the finishing stroke, for he has been beaten, but by no means crushed." He poured withering scorn on those delegates who frivolously asserted: "It is all over with the Mensheviks now." He had no difficulty in showing that the Mensheviks still had roots in the working-class movement, that they had to be fought with skill, and that all overestimation of one's own strength and, especially, all underestimation of the strength of the enemy had to be avoided. "No boasting in victory"—this was a feature of Lenin's character that helped him soberly to weigh the strength of the enemy and to insure the Party against possible surprises. FIDELITY TO PRINCIPLEParty leaders cannot but prize the opinion of the majority of their party. A majority is a power with which a leader cannot but reckon. Lenin understood this no less than any other party leader. But Lenin never became a captive of the majority, especially when that majority had no basis of principle. There have been times in the history of our Party when the opinion of the majority or the momentary interests of the Party conflicted with the fundamental interests of the proletariat. On such occasions Lenin would never hesitate and resolutely took his stand on principle as against the majority of the Party. Moreover, he did not fear on such occasions literally to stand alone against all, considering—as he would often say—that "a principled policy is the only correct policy." Particularly characteristic in this respect are the two following facts. First fact. This was the period 1909-11, when the Party, smashed by the counterrevolution, was in a state of complete disintegration. It was a period of disbelief in the Party, of wholesale desertion from the Party, not only by the intellectuals, but partly even by the workers; it was a period when the necessity for a secret organization was being denied, a period of Liquidatorism and collapse. Not only the Mensheviks, but even the Bolsheviks consisted of a number of factions and trends, for the most part severed from the working-class movement. We know that it was at that period that the idea arose of completely liquidating the secret party and organizing the workers into a legally sanctioned, liberal Stolypin party. Lenin at that time was the only one not to succumb to the epidemic and to hold aloft the Party banner, assembling the scattered and shattered forces of the Party with astonishing patience and extraordinary persistence, combating each and every anti-Party trend within the working-class movement and defending the Party idea with unusual courage and unparalleled perseverance. We know that in this fight for the Party idea, Lenin later proved the victor. Second fact. This was the period 1914-17, when the imperialist war was in full swing, and when all, or nearly all, the Social-Democratic and Socialist parties had succumbed to the general patriotic frenzy and placed themselves at the service of the imperialism of their respective countries. It was a period when the Second International had hauled down its colors to capitalism, when even people like Plekhanov, Kautsky, Guesde and the rest were unable to withstand the tide of chauvinism. Lenin at that time was the only one, or almost the only one, to wage a determined struggle against social-chauvinism and social-pacifism, to denounce the treachery of the Guesdes and Kautskys, and to stigmatize the halfheartedness of the betwixt-and-between "revolutionaries." Lenin knew that he was backed by only an insignificant minority, but to him this was not of decisive moment, for he knew that the only correct policy with a future before it was the policy of consistent internationalism, that a principled policy is the only correct policy. We know that in this fight for a new International Lenin proved the victor. "A principled policy is the only correct policy"—this was the formula with which Lenin took new "impregnable" positions by assault and won over the best elements of the proletariat to revolutionary Marxism. FAITH IN THE MASSESTheoreticians and leaders of parties, men who are acquainted with the history of nations and who have studied the history of revolutions from beginning to end, are sometimes afflicted by a shameful disease. This disease is called fear of the masses, disbelief in the creative power of the masses. This sometimes gives rise in the leaders to an aristocratic attitude towards the masses, who although they may not be versed in the history of revolutions are destined to destroy the old order and build the new. This aristocratic attitude is due to a fear that the elements may break loose, that the masses may "destroy too much"; it is due to a desire to play the part of a mentor who tries to teach the masses from books, but who is averse to learning from the masses. Lenin was the very antithesis of such leaders. I do not know of any revolutionary who had so profound a faith in the creative power of the proletariat and in the revolutionary fitness of its class instinct as Lenin. I do not know of any revolutionary who could scourge the smug critics of the "chaos of revolution" and the "riot of unauthorized actions of the masses" so ruthlessly as Lenin. I recall that when in the course of a conversation one comrade said that "the revolution should be followed by normal order," Lenin sarcastically remarked: "It is a pity that people who want to be revolutionaries forget that the most normal order in history is revolutionary order." Hence, Lenin's contempt for all who super-ciliously looked down on the masses and tried to teach them from books. And hence, Lenin's constant precept: learn from the masses, try to comprehend their actions, carefully study the practical experience of the struggle of the masses. Faith in the creative power of the masses - this was the feature of Lenin's activities which enabled him to comprehend the spontaneous process and to direct its movement into the channel of the proletarian revolution. THE GENIUS OF REVOLUTIONLenin was born for revolution. He was, in truth, the genius of revolutionary outbreaks and the greatest master of the art of revolutionary leadership. Never did he feel so free and happy as in times of revolutionary upheavals. I do not mean by this that Lenin approved equally of all revolutionary upheavals, or that he was in favour of revolutionary outbreaks at all times and under all circumstances. Not at all. What I do mean is that never was the genius of Lenin's insight displayed so fully and distinctly as in times of revolutionary outbreaks. In times of revolution he literally blossomed forth, became a seer, divined the movement of classes and the probable zigzags of the revolution as if they lay in the palm of his hand. It w,as with good reason that it used to be said in our Party circles: "Lenin swims in the tide of revolution like a fish in water." Hence the "amazing" clarity of Lenin's tactical slogans and the "astounding" boldness of his revolutionary plans. I recall two facts which are particularly characteristic of this feature of Lenin. First fact. It was in the period just prior to the October Revolution, when millions of workers, peasants and soldiers, impelled by the crisis in the rear and at the front, were demanding peace and liberty; when the generals and the bourgeoisie were working for a military dictatorship for the sake of "war to a finish"; when the whole of so-called "public opinion" and all the so-called "socialist parties" were hostile to the Bolsheviks and were branding them as "German spies"; when Kerensky was trying—already with some success—to drive the Bolshevik Party underground; and when the still powerful and disciplined armies of the Austro-German coalition confronted our weary, disintegrating armies, while the West-European "Socialists" lived in blissful alliance with their governments for the sake of "war to a victorious finish."... What did starting an uprising at such a moment mean? Starting an uprising in such a situation meant staking everything. But Lenin did not fear the risk, for he knew, he saw with his prophetic eye, that an uprising was inevitable, that it would win; that an uprising in Russia would p'ave the way for the termination of the imperialist war, that it would rouse the worn-out masses of the West, that it would transform the imperialist war into a civil war; that the uprising would usher in a Republic of Soviets, 'and that the Republic of Soviets would serve as 'a. bulwark for the revolutionary movement all over the world. We know that Lenin's revolutionary fore-silght was subsequently confirmed with unparalleled fidelity. Second fact. It was in the first days of the October Revolution, when' the Council of People's Commissars was trying to compel General Dukhonin, the mutinous Commander-in-Chief, to terminate hostilities and start negotiations for an armistice with the Germans. I recall that Lenin, Krylenko (the future Commander-in-Chief) and I went to General Staff Headquarter6 in Petrograd to negotiate with Dukhonin over the direct wire. It was a ghastly moment. Dukhonin and Field Headquarters categorically refused to obey the orders of the Council of People's Commissars. The army officers were completely under the sway of Field Headquarters. As for the soldiers, no one could tell what this army of fourteen million would say, subordinated as it was to the so-called army organizations, which were hostile to the Soviets. In Petrograd itself, as we know, a mutiny of the military cadets was brewing. Furthermore, Kerensky was marching on Petrograd. I recall that after a pause at the direct wire, Lenin'6 face suddenly shone with an' extraordinary light. Clearly he had arrived at a decision. "Let's go to the wireless station," he said, "it will stand us in good stead. We will issue a special order dismissing General Dukhonin, appoint Comrade Krylenko Commander-in-Chief in his place and appeal to the soldiers over the heads of the officers, calling upon them to surround the generals, to terminate hostilities, to establish contact with the German and Austrian soldiers and take the cause of peace into their own hands." This was "a leap in the dark." But Lenin did not shrink from this "leap"; on the contrary, he made it eagerly, for he knew that the army wanted peace and would win peace, sweeping every obstacle from its pa'th; he knew that this method of establishing peace was bound to have its effect on the German and Austrian soldiers and would give full rein to the yearning for peace on every front without exception. We know that here, too, Lenin's revolutionary foresight was subsequently confirmed with the utmost fidelity. The insight of genius, the ability rapidly to grasp and divine the inner meaning of impending events, was that quality of Lenin which enabled him to lay down the correct strategy and a clear line of conduct at crucial moments of the revolutionary movement.

Pravda. No. 34, February 12, 1924 Signed: J. Stalin |

|||||

Previous Next Stalin's speach in RealAudio Index Lenin Museum Lenin Mausoleum |

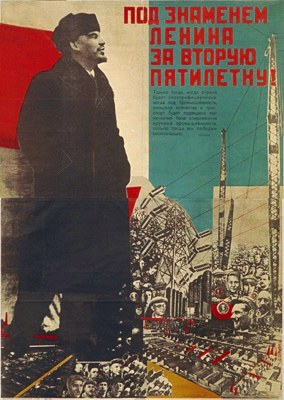

Defend Lenin Mausoleum!

Central Lenin museum.

Documents and photos about Lenin, Lenin's family and Russian Revolution

_______________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________